"There was no question that preservation as much as patriotism contributed to the economic well-being of the county."

The Plan

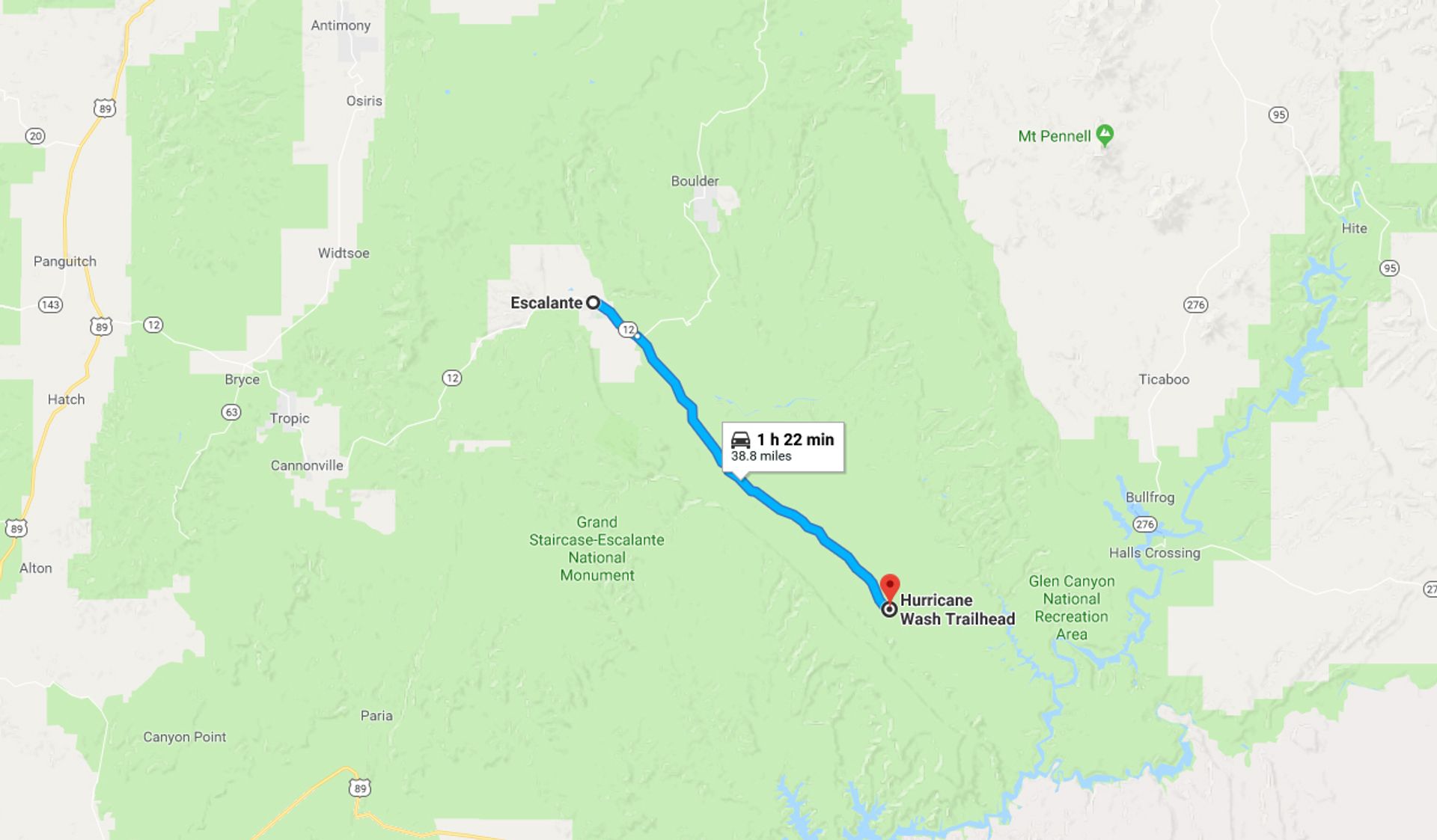

We wanted to explore a non-national park area in Utah. Glen Canyon and Escalante-Grand Staircase National Monument looked like the best option. We wanted to access Coyote Gulch using the Hurricane Wash Trailhead. Once in Coyote Gulch the plan was to hike the length of the canyon to the Escalante River.

Hiking Hurricane Wash Trail

In light of all the discussion surrounding Escalante Grand-Staircase National Monument and Bear Ears National Monument, I wanted to highlight a trip through the area, and give a sense of the park under the spotlight. Also, the trip through the deserts of Hurricane Wash and canyons of Coyote Gulch ranks as one of my all time favorite adventures to date, and has become one of my top recommended trips to date. Lastly,

Like it often is with trips to the far backcountry, getting to the trailhead is an adventure in itself. Wilderness implies being far away from people and cities, meaning that it is going to take some effort to get to most of the places I mention in my work, and Hurricane Wash is no exception. The trailhead is located 38 miles down the very bumpy Hole-In-The-Rock-Road, near the town of Escalante, Utah, smack dab in between Grand-Staircase Escalante National Monument and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

I profusely apologized to my 2002 Dodge minivan the entire way to the trailhead. An all-wheeled drive vehicle may or may not be necessary depending on the amount of rain and conditions of the roads. Continue down the road past the Zebra Canyon and the Spooky Slot Canyons, it will be tempting to stop, but I promise Hurricane Wash is worth it. It is also usually less crowded due to being so far down the road, and generally less known that the other two areas.

The trailhead will look... unflattering. In fact, the total of the surrounding area will look unimpressive. It was my first thought once we got made it to the dusty, desert access. The condition of the trailhead set the stage for a wonderful surprise later on, which I believe, is the most enjoyable part of the trip. Park in the designated parking area across the road, unload your vehicle, make sure you have everything, and start wandering.

Hiking Hurricane Wash Trail

The beginning of the journey leads directly into a dried stream bed (or wash). The dried stream becomes the trail, and you follow the winding, sun-caked, path throughout. The wash leads around strange boulders and rock structures but for the most part, remains fairly flat and easy-going. We got a late start to the hike, and only managed to hike a few miles into the expanse before the sun began to set. Camp was constructed quickly so we could explore with the remaining light in the sky.

Everything about our location was Martian, the wavy red rocks, the fiery sunset, even the plants were lime-green, fuzzy, and tendriled. I heard it described as a "Suessian" landscape, one that is fanciful and almost whimsical.

We cooked a typical dinner of noodles and watched the sun fall over the barren world. So far, we had been conservative with our water, we had seen no signs of natural springs, and we didn't know how far we needed to go before finding some. I love desert hiking, but having to carry in all the water you'll need adds to the already heavy packs. The group came to the agreement that if we didn't find water to refill our bottles by noon, we would have to turn back.

When camping in the desert, watch where you place your tent. You don't want to damage any delicate plant life, and you don't want a cactus needle spearing you and tearing your tent. Also, avoid stepping on the bright green lichen that grows on rocks, it's essential for desert life.

The Wash continued as the day before, rather bland. And I hate to say that because there is beauty in all natural settings, but it was like we were promised more. Having come all the way from Pennsylvania, we chose this trail over other national parks in the area, and only had a little over two weeks - half that was dedicated for travel time.

Getting close to noon, our agreed turn around time, our water was getting low and the hot desert sun was unrelenting. Suddenly, the Wash started to descend and the red rocks around us closed in. It happened quickly, the canyon walls swelled well above our heads - evidence of a powerful ancient river that once was.

With every step, the canyon walls grew. I realized that from above, the canyon was too narrow to detect, making it indistinguishable from the terrain. It was truly hidden until you fell in. It was like walking into another dimension, within twenty minutes, the landscape and scenery were completely different than the Wash - we had entered Coyote Gulch.

Hiking Coyote Gulch

There had been some green in the desert, but only in form of the heartiest desert shrubs. The kind of vegetation that makes you regret stepping off the path. When we rounded the first bend in the long corridor, the canyon burst to life. Light green healthy flora flooded the floor and contrasted harshly off the red wall in front of us. Signs of life suggested water was near.

We followed the greenery until we found ourselves sloshing over the smallest of streams. A seam in the rocks bubbled a spring to life. The stream grew larger every yard we followed it. A shady spot saved us from the sun and we decided to finally refill our bottles. From this point on, we were never further than fifty feet from water.

I can’t stress the ease of this trip, no leg breaking climbing, no lung popping elevation, unlimited access to water, amazing views, and an eternally half shaded path - we had made it to Coyote Gulch. It was almost casual. The canyon had created an Eden in an otherwise hellish landscape above, who would have guessed heaven was underneath hell?

The trail was along the stream, in a few places the stream became the trail. At this point we had taken off our boots and completed the rest of the trail barefoot. Never have I had the luxury of hiking barefoot, before of after this trail.

The Jacob Hamblin Arch

For a while the trail continued through the canyon, getting slightly more ‘jungly’ in some areas where the water pooled. It was the opposite of exposed hiking. Out west, when you are on the cusp of the ridge, you can see everything for dozens of miles, including (if it's not too far away) your destination. You can see all of the obstacles between you and the end. Here, however, you could only see as far as the canyon allowed. Every twist and bend was a mystery, and there was immense pleasure from each surprise. But the greatest of all was the Jacob Hamblin Arch. The massive wonder was waiting for us behind what seemed to be any other bend.

It is nearly impossible to show the true scale of the arch without relying on the size of objects around it. Adult trees were dwarfed as the main arm of the arch eclipsed the top of the canyon wall. I climbed, what I thought a small hill, underneath the Great Arch to get a better look.

“May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view.”

We rested and ate in the shadow of the mighty arch. The Jacob Hamblin Arch was one of the few places I thought may never be topped as far as hiking experiences. I was humbled in a place I had never even heard of before as I sat abashed in its umbra and watch people play, slightly irreverently on the cathedral-like structure. But of course, I was wrong, and was immediately proven that there was yet more to see in the corridor of the Coyote.

I didn't know, but Coyote Natural Bridge was less than a mile away, yet another incredible natural design by wind and time. We enjoyed the company of the water under the bridge, and splashed the sand off of our feet.

The Way to the Escalante River

A little further past Coyote Bridge, we found an extremely dense area of vegetation and went off the path to investigate. Again, another convenient aspect of the trail is that it was nearly impossible to get lost. Being in a canyon, you could really only go so far before hitting an inescapable wall. In an effort to avoid some poison ivy we found ourselves scaling a low part of the wall. Once we were up the only way down was to attempt to gracefully fall back into the brush - which we managed to do. We found, hidden towards the back of the canyon wall, a dark, deep, cold, lagoon. Someone later told us it's called ‘The Black Lagoon'. From the trail, it could have easily been missed. The lagoon was our first bath in over a week, and a sanctuary from the midday heat.

The Lagoon cooled us long enough to get a few more miles in before it started getting dark. It’s customary to set your camp at least a few hundred feet away from the trail, but the canyon was so narrow, that we didn't have a choice. Also, you don’t want to be near water for various conservation and ecological reasons, as well as the chance of a flash flood. In this one instance we were forced to camp near the trail, so we made sure to pack up early in the morning.

After a restful night, we were determined to finish hiking the Gulch before sunset. We hid our bags among some rocks, and continued lightly for the rest of the morning, meaning to come back for our gear when we doubled back to leave the canyon.

Dropping your bags doubles your speed. We flew threw the rest of the canyon in record time. It was also a good idea, because the canyon grew deeper and the water ran faster. It required some bouldering and swimming to make it the rest of the way. Along the end of the route we found waterfalls, ravines, and reeds.

As suddenly as the canyon started, it ended. As we rounded a bend, the canyon walls dropped and opened up to a valley. The creek we were following emptied into the Escalante River and our hike was finished. We needed to get back to our gear and navigate our way out of the Gulch. Some trips end with, "that was fun. where do we go next?" but Escalante ended with, "when can we come back?"

Visitation and Preservation

A few closing notes about the area, the trail, the history, and the parks:

I purposely left out a major piece of the story of the park - the history of the Coyote Gulch. The entire canyon was home to people thousands of year ago, and there is abundant evidence of that throughout the trail. There are petroglyphs, drawings, ancient dwellings and petrified artifacts littered all around the canyon. I decided not to include the places and pictures of these artifacts to protect them, however, I have to say that I have never been prouder of the backpacking community. As far as I could tell, the areas were left alone and only enjoyed by people’s eyes. Maybe the backpackers left the artifacts because they didn't want to add weight to their bags, but I am convinced it is because most people recognize the significance of the relics.

Escalante Grand-Staircase and Bear Ears National Monument are currently under fire from the administration, the media, social media, and passionate environmentalists. The plans to reduce the size of the monuments are at the very least controversial. It was clear to me when I visited, that the federal government just does not have the resources to protect such a large area. An area that deserves to be protected should have the proper funding and personal to do a good job. That is just not the case with Escalante.

Years ago, when the famous Hetch Hetchy Valley was being considered to be turned into a dam, Alan Chamberlain suggested the following: “It seems to me that we should try in this connection to stimulate public interest in National Parks by talking more about their possibilities as vacation resorts,” he remarked, similarly emphasizing visitation over wilderness. Indeed, only “if the public could be induced to visit these scenic treasurehouses would they soon come to appreciate their value and stand firmly in their defense.”

Visitation to these wilderness places should be encouraged. It will give people a reason to defend the area, it will give proper funding to protect the land, life and artifacts in the canyons, and it will take strain off of the heavily used national parks in the area.

Visitation is the key to protection. Even John Muir, one of, if not the most prolific conservationists agreed on the construction of a road into the Yosemite Valley, saying “To save the [Yosemite] valley, indeed the entire park system, seemed to hinge on greater visitation.” Through the entire 26 miles I saw less than a dozen people. If done in temperance, visitation can benefit the area more than letting it sit idle.

“The love of wilderness is more than a hunger for what is always beyong reach; it is also an expression of loyalty to the earth, the earth which bore us and sustains us, the only paradise we shall ever know, the only paradise we ever need, if only we had the eyes to see.”